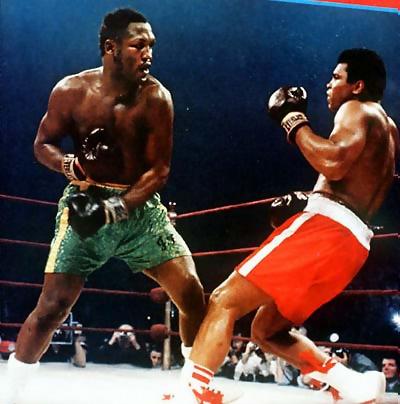

Frazier gave up 10 pounds in weight, four inches in height, and nine inches in reach. To win, he was going to have to penetrate Ali's long-range defenses. To penetrate, he was going to have to take some serious hits. To survive those hits, he was going to have to bob and weave from the waist, do it repeatedly, and do it all night, an exertion of nearly inhuman persistence and energy.

In the first four rounds, Ali tried to inflict enough hurt on the dogged Frazier to knock the drive out of him, if not knock him out altogether. Frazier took his lumps, literally, and kept on coming. "Visions of King Kong atop the Empire State building deflecting the bullets of the attacking biplanes raced through my mind," remembers Dr. Ferdie Pacheco. Ali was winning the rounds, but losing the fight.

In round five, Frazier, still hammering, forced Ali off his toes and into the ropes where he set up shop. "Frazier falls in six," Ali had promised before the fight. Frazier would have none of it. Frazier shot out of his stool at the start of the sixth, shouting, "C'mon, sucker. This is the round. Let's go." In rounds seven and eight, as a form of psychological warfare, Ali started mocking Frazier and playing to the crowd.

"Don't you know I'm God," Ali yelled at Frazier to discourage him.

"God, you in the wrong place tonight," Frazier shot back. "I'm kicking ass and taking names."

In the ninth, Ali let it fly. Students of the sweet science consider it perhaps the most dazzling one-round exhibit they have ever seen. "Frazier's face was falling apart," remembers Pacheco. His resolve, however, was indestructible. If that kind of round could not plunge Frazier "into a well of despair," asks sportswriter Mark Kram, "what in heaven or hell would – point-blank fire from a gun muzzle?" Ali, who gives Frazier his due in the recounting of this fight, remembers thinking, "Now I know he'll die before he quits."

Pacheco judged Ali the winner of the 10-round fight. The problem for Ali was that this one had to go 15. Frazier would not stop. "Hit me, I hit you," Frazier muttered, "I don't give a damn. I come to destroy you, Clay."

The fight turned around in the 11th. The Ali camp called it the "Gruesome Eleventh." Frazier caught Ali with a wicked, crooked-arm left hook early in the round and sent him staggering to the ropes. "Ali's legs shake," commented Jose Torres from ringside. "He was tagged. That was to the button." Ali survived the round but lost all momentum. By the start of the 15th, more people at the Garden were chanting "Joe ... Joe ... Joe" than "Ali ... Ali ... Ali." "I'd proven I was no fodder for no Cassius Clay fairytale," remembers Frazier, who understood better than anyone how the Ali myth was being spun.

"The hell of the previous 14 rounds was meaningless," Pacheco observes. As most saw it, including my friends and I in a Gary, Ind., theater, the fight hung on the 15th. Frazier left nothing to doubt. He cleared the ground with both feet on a looping left hook that caught Ali flush on the right side of his face. "Boom," says Frazier with deadly glee, "and there it was – Mr. Him on his butt, his legs kicking up into the air – the very picture of a beaten man."

In Gary, we watched that knockdown on the large screen from the top of the aisle near the exit. Ali somehow staggered to his feet, his jaw now swollen to twice its size, and stayed upright until the bell. Even Frazier admits that Ali "showed big heart." Big heart or not, no one in Gary doubted the outcome. One angry black man stormed by us at the exit, the depth of his affection for Ali no thicker than his wallet. "Muhammad Ali, my ass," he growled. "That's Cassius Clay."

The decision was unanimous. Frazier raised his hands in victory, thanked the Lord, and with a bloody mouth sneered at Ali, "I kicked your ass." Referee Arthur Mercante thought it the most vicious fight he had ever seen. Mark Kram calls it the "most skillful." And by all accounts, it was the most dramatic. "I was 27 years old, and there would never be another night like it in my life," remembers Frazier. He spent the next three weeks in the hospital.

A more just world would have celebrated Frazier as the "Cinderella Man" of his era: the 12th child of a rural Gullah family, who hightailed it out of the South on his own at age 15, developed his superior strength hauling carcasses in a slaughterhouse, and prevailed over a more privileged, more popular, more physically gifted opponent through an iron display of will not seen before or since.

From the beginning, however, careful observers knew that the story wasn't going to play out that way

In the ring, Joe Frazier was a bull who didn't need a red cape. Provocation or prodding wasn't necessary for him to come charging after the man in front of him, his head down, his fists acting as sharp horns and inflicting similar damage.

Joe Frazier won the first of his three epic battles with Muhammad Ali.

It was that relentlessness -- the near-total abandonment of duck-and-cover, the philosophy that one must absorb punishment before one can properly distribute it -- that defined Frazier's boxing career and has defined his life. It carried him to an Olympic gold medal and to the heavyweight championship of the world.

And it was that relentlessness that made him the perfect foil for his nemesis, Muhammad Ali. Discussing Frazier's boxing career without bringing up Ali is like talking about Neil Armstrong without mentioning the moon. The two are forever linked, thanks to their three timeless bouts -- Frazier won only the first, and the third was a near-death experience for both of them -- the contrasting styles with which they fought, and the vitriol they hurled at each other for so long.

For years, Frazier has voiced his bitterness over the way Ali had insulted him, over how Ali had called him "ugly," "a gorilla," and an "Uncle Tom." His anger was never in fuller view than when Ali, stricken with Parkinson's disease, lit the Olympic flame at the 1996 Games in Atlanta, and Frazier said he would have liked to have "pushed him in."

"Technically the loser of two of the three fights, [Frazier] seems not to understand that they ennobled him as much as they did Ali," wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Halberstam, "that the only way we know of Ali's greatness is because of Frazier's equivalent greatness, that in the end there was no real difference between the two of them as fighters, and when sports fans and historians think back, they will think of the fights as classics, with no identifiable winner or loser. These are men who, like it or not, have become prisoners of each other and those three nights."

Born on Jan. 12, 1944, in Beaufort County, S.C., Joe was the 11th child of Rubin and Dolly Frazier. The Fraziers had a 12th child, David, who died of diphtheria at nine months old.

Rubin was a sharecropper, who, according to Frazier's 1996 autobiography, "Smokin' Joe," ran a moonshine still and grew "this musk, which I figure now must've been tobacco or marijuana."

By 1959, Joe was on his own, and that year, at 15, he moved to New York to live with an older brother, Tommy, and Tommy's wife, Ollie. He had a difficult time finding work, so difficult that he began stealing cars and selling them to a Brooklyn junkyard for $50 apiece.

"It got to a point, finally, where I was just too embarrassed to keep leaning on my brother," Frazier wrote. "I decided to head to Philadelphia, where I had relatives that would put me up, and see if my luck would change."

Did it ever. While working at a slaughterhouse, he punched sides of beef in a refrigerated room (giving Sylvester Stallone some inspiration for "Rocky") and took up bona-fide boxing in December 1961 when, 30 pounds overweight at 220, he entered a Police Athletic League gym in the city.

Joe Frazier lands one of his trademark left hooks.

A few months later, he met Yank Durham, a trainer at the gym. Durham turned Frazier into a champion, shortening his punches, improving his leverage, adding speed and power to what would become Frazier's signature weapon -- his famous left hook.

Frazier began traveling around the country, boxing regularly. He was the Middle Atlantic Golden Gloves heavyweight champ for three straight years but lost to Buster Mathis in the finals of the 1964 U.S. Olympic Trials. However, during a subsequent exhibition bout between the two, Mathis injured his hand, paving the way for Frazier to replace him at the Olympics in Tokyo.

Despite fighting the final bout with a broken left thumb, Frazier won gold at the '64 Olympics by decision over German Hans Huber.

Later in the year, Frazier learned he had cataracts in his left eye. Though he was visually impaired, he turned pro as some Philadelphia boxing fans formed a group called Cloverlay and bankrolled him to the tune of $20,000.

Frazier's pro debut came on Aug. 16, 1965, and within 12 months he was 11-0, with every victory coming by knockout.

While Ali defied the U.S. Army in 1967, refusing to be inducted, the WBA stripped him of his heavyweight title. Frazier bypassed an eight-boxer tournament the WBA established to determine a new champion -- a tournament that included Floyd Patterson, Jerry Quarry and Jimmy Ellis -- and padded his record against other fighters.

He knocked out Buster Mathis in the 11th round in 1968 to become the New York State champion, floored Quarry in eight rounds in 1969, and dispatched Ellis, the WBA champ, in five on Feb. 16, 1970, to become the undisputed heavyweight champion.

Then Ali returned, as his boxing license was reinstated. On Dec. 30, 1970, the two signed to fight, and the name-calling began.

"A white lawyer kept him out of jail. And he's going to Uncle Tom me," Frazier wrote in his autobiography. "THEE Greatest, he called himself. Well, he wasn't The Greatest, and he certainly wasn't THEE Greatest. . . . It became my mission to show him the error of his foolish pride. Beat it into him."

On March 8, 1971, in the "Fight of the Century" at Madison Square Garden, Frazier landed a left hook in the 15th round that sent Ali careening to the canvas. The unbeaten Frazier won a unanimous decision as he handed Ali the first defeat of his pro career.

Frazier successfully defended his title against Terry Daniels and Ron Stander (both on early-round TKOs) before meeting George Foreman on Jan. 22, 1973, in Jamaica. Stronger and quicker, Foreman knocked Frazier down six times in the first two rounds before the fight was stopped. Frazier's title was gone.

A year later, he met Ali again, in a non-title bout. On Jan. 28, 1974, in a fight to determine who would get the next shot to dethrone Foreman, Ali won a decision in Madison Square Garden, though Frazier and several sportswriters, including The New York Times' Red Smith and Dave Anderson, thought he had won.

With the cataract in his left eye growing increasingly worse, he defeated Quarry and Ellis again, then agreed to fight Ali one final time, on Oct. 1, 1975, in Manila. In arguably the greatest heavyweight bout in boxing history -- Ali called it the "closest thing to dyin' I know of" -- the two men clubbed each other with their fists for 14 rounds. Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, wouldn't let his fighter come out for the 15th.

"Once more," Sports Illustrated's Mark Kram wrote of the "Thrilla in Manila," "had Frazier taken the child of the gods to hell and back."

Frazier finished his career with a 32-4-1 record and 27 knockouts.

Frazier retired after his next fight -- when he was knocked out by Foreman in the fifth round in 1976. He came out of retirement five years later for one fight, a draw with a former convict, Floyd "Jumbo" Cummings, and finished his career with a 32-4-1 record and 27 knockouts.

Frazier lives in Philadelphia, owns and runs a gym there. His health is not the best as he has diabetes and high blood pressure. He and his nemesis have alternated between public apologies and public insults.

One exchange came in 2001 after Ali told The New York Times he was sorry for what he said about Frazier before their first fight. At first, Frazier accepted the apology, but then …

"He didn't apologize to me -- he apologized to the paper," Frazier said in a June issue of TV Guide. "I'm still waiting [for him] to say it to me."

Today on his sixty-first birthday, and thirty-four years after "The Fight of The Century", it is my opinion that former heavyweight champion Joe Frazier gets lost in the overall picture of history’s greatest heavyweight champions. The way I see it, Joe Frazier can lay claim to something no other fighter in boxing history can: that is he was the winner of the biggest and most celebrated fight in boxing history. And it's definitely not a reach to say that the first fight between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali was the biggest sporting event of all time.

In what was his career defining fight, Joe Frazier was better prepared mentally, physically and strategically for Ali, more so than any other fighter I have ever seen for an opponent. Only because of the Herculean effort of Frazier was Ali the loser in the most anticipated fight in history. Only Ali could recover from losing such an event and go on to be bigger than he would have been than if he won. However, what continues to mystify me is how Frazier is often overlooked and underappreciated, not to mention underrated. That’s unbelievable in today's sporting world where everything is usually overrated based on one great fight or game. Yet Frazier, who won the fight that mattered most, is overlooked. Talk about being born at the wrong time. I thought that only applied to Jerry Quarry.

Maybe the Frazier who defeated Quarry twice should be linked to him for another reason: being victim to the calendar and having a lifetime to think about it. Many boxing aficionados have remarked that it was Quarry's misfortune to be in his prime at the same time that Ali and Frazier were at or close to theirs. I think it can just as easily be said that Frazier had the misfortune of being champion when Ali was larger than life and George Foreman was at his physical peak. If you compare Frazier and Ali strictly as fighters, there isn't much separating them. All three fights between them were close and went down to the wire with some seeing both of them as being the winner in their first two bouts. In terms of fighting styles, Ali's strengths were Frazier's weakness and vice-versa, which is why their fights were so grueling and took so much out of each man.

When comparing Frazier and Foreman as fighters, Frazier was actually the better fighter. However, he didn't match up with Foreman from a style vantage point. George Foreman and Joe Louis were the two most difficult opponents in heavyweight history to fight while employing a pressure style. Unfortunately, Frazier, just like Dempsey, Marciano, and Tyson, could only fight effectively moving forward forcing the fight. Foreman was the one fighter that when Joe coming out "Smokin’", it proved hazardous to Frazier’s health. Frazier's loss to Foreman no doubt damaged his image as a great fighter. I would love to have seen how Dempsey, Marciano, and Tyson, who in their careers combined never fought a fighter anywhere near the puncher that Foreman was, would have done against the one that made Frazier an ex-champ. I have a hard time envisioning the results being any different.

Over the years I've had to continually remind some that Joe Frazier was the ultimate catch and kill fighter. What I mean by that is nobody applied more pressure and cut off the ring better than he did.

It was Joe Frazier, not Dempsey, Marciano and Tyson, who developed the blueprint on how to make a mover/boxer fight flatfooted and on the inside because the ring space they needed to move and box evaporated. And Frazier did this successfully versus the best escape artist who has ever lived, Muhammad Ali. And I believe he would've been successful cutting off the ring on any version of Ali.

Remember, during the sixties Ali never faced a fighter who could get past his jab and take it to him inside. Had Marvin Hagler been able to cut off the ring against Sugar Ray Leonard half as effectively as Frazier did against Ali, Leonard would have retired forever after their bout.

Against Ali, Frazier forced him to either fight, hold, or use his legs to try and stay away. When Ali tried moving against Frazier, he paid a price with his stamina and eventually had to fight Joe inside, which played to Frazier's strength. On the inside, Frazier's hands were very fast, something that has always been overlooked. Something else that seems to have been forgotten was his foot speed. Sure, his legs didn't appear to move fast, but he got on top of his opponents right away. And with all the hard punches he was throwing, he was damn near impossible to move off. If you managed to slip away - and only Ali had enough movement to succeed with that tactic - he was right back on you again within seconds. Frazier had very deceptive hand and foot speed.

Muhammad Ali's jab was his security blanket and defense. No fighter made him miss with so many jabs as Frazier did over the course of 41 rounds. Sure he landed and scored with plenty of them, but when compared to how many he was forced to throw to land what he did, I'll bet the connect percentage would surprise many fans and fight observers. Frazier's bobbing and weaving was also much more effective in taking away a good jab than Marciano fighting out of a low crouch or Tyson's overrated and basic hands up, side-to-side, peek-a-boo movement. And it also required much more skill to execute without getting your head knocked off in the process.

If you doubt that, try holding your hands up and moving side-to-side, and then try bobbing and weaving using your waist and legs to get under and inside of punches. I've done both and it's no contest as to which is harder and more effective. Roberto Duran in his prime is the only other fighter I've seen do it as fluidly and effectively as Frazier did. Maybe that should tell you something about why we don't see many swarmers today adopting that tactic. It's too hard and requires endless stamina and conditioning.

Not only did Frazier make Ali miss with the fastest jab in heavyweight history, he made him pay - scoring with massive left hooks to his head and body when he missed. Ali says to this day Frazier was hard as hell to find and hit. The problem is that all anyone ever remembers is Frazier's puffed and bruised face after their fights. As if Ali came out of their fights unmarked.

During his career, Joe Frazier fought every fighter out there. As early as his 11th pro fight he took on Oscar Bonavena, who had close to 30 fights under his belt. Frazier was dropped twice in the second round against Bonavena. When he got up from the second knockdown there was a minute left in the round and he was never close to going down or being stopped the rest of the round or fight. So in reality only George Foreman stopped him, with no other fighter coming close, until Ali shut his eyes in Manila.

Frazier's two wins over Bonavena and early stoppages over Chuvalo, Quarry twice, Ellis twice, and Foster once, rank close to the level of opposition that many other greats faced. However, his convincing win over an undefeated Muhammad Ali two months after his 29th birthday clearly puts him on par or slightly ahead of any other heavyweight great except Ali. And Joe fought him three times, which is equal to the best three fights of any other past great. After clearly defeating Ali in their first meeting, the second fight was close, probably 7-5 in rounds. It wasn't a cakewalk for Ali like some think, and 7-5 is more realistic than 8-4. And their third fight, "The Thrilla in Manila," was three fights in one. Ali had control in rounds one through five, Frazier had control in rounds six through eleven, and Ali took over in rounds twelve through fourteen.

Over the years I've had to continually remind some that Joe Frazier was a better two-handed fighter than given credit for. Although he didn't have a very good conventional straight right hand to the head, his right hand to the body was dynamite. Frazier also carried his punch from round one to fifteen, something only Louis and Marciano shared. And only Marciano got better and stronger like Frazier did as the fight progressed.

Over the years I've had to point out that only two fighters ever defeated Joe Frazier. Muhammad Ali usually ranks number one or at worst number two behind Joe Louis among history’s greatest heavyweights, and in three fights against Ali, Frazier gave him a life and death struggle and won the biggest of the three bouts.

The other fighter to beat Frazier is George Foreman and he did it twice, stopping him both times. Foreman is probably the strongest and hardest punching heavyweight champ of all time. If he punched with the proper technique, it would have been illegal to allow him to fight mortal fighters. After a ten year retirement he came back and beat the man who beat the man to win the title. And Foreman wasn't anywhere close to the physical fighter in the 1990s that he was in the 1970s. And in a head-to-head match up, the ‘70s Foreman would stop the ‘90s version.

I have often thought about how other past greats would have fared had they fought the same Muhammad Ali and George Foreman that Frazier did in five fights. I haven't a morsel of doubt that their career image and perception just might have been a little more tarnished than is the case.

Some remember Frazier's career because he lost to Foreman in two rounds. Yet a 41-year old Foreman had a prime Evander Holyfield holding on at the end of their title fight in 1991. During the years of his return to the ring, 1989 to 1991, Foreman constantly used the media to challenge Mike Tyson. Some fans try to ignore this or say Tyson didn't want to hurt Foreman and that's why he never fought him. How far does one have to go to convince them to believe that? The fact is Mike Tyson wanted no part of fighting the same 41-year old Foreman who Holyfield fought. I know this because I heard Bobby Goodman say it in front of me to George Benton and Lou Duva after a press conference in Atlantic City for the Evander Holyfield-Seamus McDonagh fight in June of 1990. Tyson himself said it in Ring Magazine in 1991.

Larry Holmes lost his heavyweight title to light heavyweight champ Michael Spinks, all be it at the end of his career, and it didn't hurt his standing as a great fighter. Mike Tyson's legacy is based on knocking out that same light heavyweight champ seven years after he won the light heavyweight title. Yet Frazier's two round mutilation of light heavyweight champion Bob Foster - who is at least on a par with Spinks - two years after he won the title, is considered no big deal.

Joe Frazier never lost to a Michael Moorer or was never knocked out by the likes of Buster Douglas or Hasim Rahman. Over the last hundred years, only Jeffries, Tunney, Marciano and Frazier never lost to a fighter they should have beaten. Not once. Frazier was also never counted out, something that cannot be said about Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Sonny Liston, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, Mike Tyson and Lennox Lewis.

For years the main highlights of Frazier’s career that have aired on boxing specials and documentaries are Foreman lifting him up with a monstrous right uppercut and Ali hammering him with combinations during the fourteenth round in Manila. That's not the only Joe Frazier I remember.

If this writing is too soft on Joe Frazier for anyone’s liking, I’ll accept that. However, anyone who believes this to be the case should recognize that many writers, historians and fans have slighted the career and accomplishments of Joe Frazier. And in an era that every supposed great is over-hyped and overrated, Joe Frazier is consistently underrated.

I was told something by someone who was involved with The Cloverlay Corporation that managed Joe Frazier. I will paraphrase it since I cannot quote the exact words. When Frazier was about to begin his first training session after signing the contract on December 30, 1970 to agree to fight Muhammad Ali on March 8th 1971, Yank Durham, Joe’s manager, trainer and some say father figure, said: “Joe, if you beat this guy, the road the rest of your life will be paved forever no matter what you do. But if he beats you, you'll never get the respect you deserve as heavyweight champion. History will look at you as a caretaker champion who just held the title for him until he got straightened out with the government. And remember, Joe, Clay doesn't want to just beat you. He wants to humiliate you and embarrass you. Beat this guy Joe and they can never take it away from you.”

I haven't heard anyone try to take Frazier's monumental victory away from him, but too many have forgotten about it. Only one fighter won the biggest fight in boxing history. And his name was Smokin’ Joe Frazier.

Boxing fans should never forget it

In the proud, tough, indomitable fighting city of Philadelphia, a statue stands at the top of the Philadelphia Art Museum's 72-step entrance.

It is nine feet tall and made of bronze. It is a picture of the fictional Rocky Balboa, his arms raised in victory. The statue, commissioned by Sylvester Stallone in 1982 for his movie, Rocky III, has been alternately a source of bemusement and downright embarrassment for Philadelphians - and especially Philadelphia fight fans - for twenty-two years now.

But sadder even than the atrocious ugliness of the Stallone fabrication, is the fact that at least a generation of young burghers has grown up with the belief that Rocky Balboa was somehow a real person and Philadelphia's most significant contribution to heavyweight boxing.

In another part of town, along dilapidated North Broad, is an old and decrepit gym. That gym is ravaged by neglect now, and it is empty. This moribund structure was once Joe Frazier's gym, but there have been no commissions by rich Hollywood power-brokers or by well-connected politicians to restore it to its former glory. Instead, it sits there and rots while "Rocky" - a figment of a struggling screenwriter's imagination - guards the entrance to one of Philly's architectural landmarks.

The man who once owned this grimy place, like the building itself, has been consigned to the shadows, even though he is one of the greatest heavyweight champions of all-time.

I first became aware of Joe Frazier not long after I first became aware of Muhammad Ali.

I was quite young at the time and I was watching one of Frazier's fighters on TV. One of the announcers talked about a man in the corner of this now-anonymous fighter who'd been the toughest man Muhammad Ali had ever fought. Given all I had heard about Ali in my young life, this latest revelation made this still unfamiliar fellow (I eventually learned that his name was Joe Frazier) very interesting to me - and I resolved to learn more about him. What I learned was impressive: This man had been the first man to defeat Ali (in 1971); he had been heavyweight champion of the world - in whole or in part - for nearly five successive years; in the golden age of the heavyweight division, he had successfully defended the sports' most coveted crown nine times; he had gone undefeated over the first seven-and-a-half years of his career; he came within a whisker of winning, arguably, the greatest fight of all-time. The more I learned about Joe Frazier, the more apparent it became that his place in the history of the sport was under-appreciated and, too often, utterly ignored. This article is as much about why that is, as it is an appreciation for the kind of fighter and champion Joe Frazier was.

When Frazier began his professional career in August of 1965, the heavyweight championship of the world was held by some guy named Ali. Muhammad Ali, it soon became apparent, was a very special champion: he was dashingly good-looking; he appeared the very preening symbol of black pride; his defiance and irreverence seemed to mirror the defiance and irreverence of the dirty white kids at college campuses all across America who came to identify with - and, yes - love him. He said provocative things and was a consummate showman in an era when fighters were still primarily boring and bland and knew not a whit about self-promotion. Ali, in a nutshell, was the perfect heavyweight champion for one of the most turbulent decades in American history.

Joe Frazier, on the other hand, was more like your parents were: he claimed no movie stars as friends; he joined no strange cults; he was not tall and beautiful; he was certainly not loud and bombastic. All Frazier ever resolved to do was to become a great heavyweight and then a great heavyweight champion. He was out of place in the frenetic Sixties. And the baby boomers, who were coming in swarms to take over the sporting media, made sure he never forgot it.

When Ali was exiled from boxing in 1967, Frazier became, indisputably, the best heavyweight fighter on the planet. He cut a destructive swath through the heavyweight division, conquering - sometimes brutally - the best fighters the division then had to offer: Bonavena, Machen, Jones, Quarry, Chuvalo. He became feared; his left hook - the left hook that nearly blinded ironman George Chuvalo and effectively ended the careers of Machen and Jones - became legendary. By the time Ali finally got back into the fight game in late 1970 after three-and-a-half years away, Frazier was firmly entrenched as the division's kingpin. But to the boomers, he was still an inarticulate interloper who held Ali's belt.

On March 8, 1971, Muhammad Ali finally got his shot at the man holding "his" championship. In the years that have followed, so much has been written about Ali-Frazier I that it seems almost redundant to write about it again here. Nonetheless, in the long history of professional prize-fighting, this night - and this fight - has a seminal place in boxing lore. As it turned out, it was a night that belonged to Joe Frazier; for three minutes of every round for fifteen brutal and unforgettable rounds, he fought with all of the desperate energy of a frightened animal trying to escape a strangling thicket.

Ali, his body and his skills not quite what they had once been, fought magnificently as well; indeed, there were many times when it seemed that Frazier could not possibly endure much longer the head-whipping he was receiving. But when the night was over, Frazier - courtesy of a classic knockdown in the fifteenth - was still the heavyweight champion of the whole wide world while Ali was still left to wander in the boxing wilderness. From this point onwards, the baby boomer press corps - which had long-before adopted Ali as their "guy" - never let Frazier forget that he had committed the unpardonable sin of whipping their hitherto unblemished symbol of Sixties defiance. When Muhammad got nasty both before and after Ali-Frazier I, the press corps indulged him; sometimes - as in the case of the slithery Bryant Gumbel - they even not-so-subtly encouraged him in his rants. Frazier, lacking Ali's political power base and not nearly as articulate as his tormentor, was more or less forced to suffer in silence.

Fast forward four-and-a-half years. It is the fall of 1975. America is out of Vietnam and Nixon is out of the White House. Joe Frazier has lost his heavyweight title to George Foreman and Ali has regained it at George's expense in Africa. By now, the relationship between the two men is truly poisonous. Ali is given to grotesque pantomimes of Frazier in his public workouts in which he portrays Frazier as an imbecilic gorilla desperately seeking lost bananas. On international television, he calls Frazier filthy and stupid and smelly. As if that isn't bad enough, he makes fun of Frazier's speech and runs around Manila with a rubber gorilla that he pulls out at a moment's notice to the bemusement - and sometimes delight - of media onlookers. Once again, the boomers in the press rows give Ali a free ride while Frazier, who has determinedly worked his way back into the title picture, is dismissed as an "easy mark-slash-punching bag" that Ali will quickly dispose of. When the fight arrives, Muhammad is a solid 2-to-1 betting favorite.

And so we have Manila. It is not long -it takes about three rounds - before Ali discovers that his own ego has led him into a deadly trap; by the sixth round, he is trapped in a primordial battle for survival with a man who hates him and who has come to beat him to death, if possible. For fourteen rounds - forty-two minutes - the two men fight beyond any comprehensible limit of human endurance. At one point around the tenth, Frazier appears to have the fight won; then Ali, reaching deep into unfathomable reserves, slowly but irreversibly turns the course of history. It is finally over after fourteen rounds when Eddie Futch decides that a bloodied, battered but still willing Frazier has had enough. After being sent straight to hell by Frazier for the previous several rounds, Muhammad Ali has rallied to win the greatest heavyweight tilt in history.

All of this takes us to today.

Nearly thirty years after their last and most brutally draining bout, it is clear that many in the sports media still favor Ali over Frazier. As much as I love Ali, as much as I appreciate how much he has given the sport, the bias is far too pronounced and it is troubling. Too often, it seems, the boomers love Muhammad for all of the wrong reasons; namely, they love him because his youthful sensibilities and excesses mirrored their own wanton sensibilities and excesses "back in the day."

Frazier, who never publicly rebuked anyone's political leanings during his time as champion, is only mentioned in news dispatches when he is taking an ill-considered swipe at his latest girlfriend or pursuing ill-advised legal suits over bad real-estate investments. (This is in marked contrast to the worshipful treatment Ali receives from the Thomas Hausers and David Remmicks of the world). Moreover, while Ali is - quite rightly, I might add - acclaimed as the Greatest Heavyweight Champion of All Time, Frazier is frequently ranked below the likes of Rocky Marciano and Jack Dempsey by fight historians; for my money, these are two men who wouldn't get out of the dressing room against a prime Smoking Joe.

So what is my resolution? What it is that I would like to see done? Well, quite frankly, I would like to see a little more respect for Frazier, for one thing. Over the last couple of years, he and Ali have patched up their differences - at least to the point where they no longer loudly exchange insults whenever the opportunity presents itself. Given that the combatants themselves have finally decided to lay down arms, the often self-congratulatory media needs to take that next step itself and stop punishing Frazier for defeating Ali that long-ago night in MSG. In addition, I would like to see boxing historians acknowledge Frazier's important place in boxing history. To think that Jack Dempsey - who never beat anyone of historical consequence during his overblown reign as heavyweight champion - is consistently ranked in the top five ever while Frazier is habitually ranked behind him and - heaven forbid! - Mike Tyson, is absurd; Frazier deserves more regard than that.

If these two things are finally done (and I remain hopeful) then you will never see me climb back up onto my soapbox in this manner again (unless it's to take a dig at Roy Jones, Jr.).

But not all birthdays are created equal, as the continuing disparity in the level of public recognition accorded former heavyweight champions Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier this month demonstrates.

Ali turns 65 Wednesday, and the date will be observed with a smorgasbord of tributes. ESPN Classic, in fact, got an early jump on the party, beginning 52 hours of programming on Sunday. Wednesday, though, it's all Ali all the time, with a 24-hour marathon on the cable channel whose mission seemingly is preservation of the Ali legacy.

Replays of seven Ali bouts - 1964, Sonny Liston I; 1965, Liston II and Floyd Patterson I; 1966, George Chuvalo; 1974, George Foreman; 1975, Chuck Wepner and Frazier III - will be televised in their entirety, to be followed by "Ali Rap," a recent ESPN special; "Ali's Dozen," a compilation of Ali's best and most important rounds; and "Ali's 65," an ode that dwells on Ali's effect on society.

"No one represents what ESPN Classic is all about more than Muhammad Ali," said John Papa, Classic's vice president of programming.

You might have noticed that one Ali bout that won't be televised is his March 8, 1971, showdown with Frazier in Madison Square Garden, the opening act in their three-part passion play that arguably was the most anticipated boxing match of all-time. In that pairing of undefeated superstars, Smokin' Joe floored Ali with a leaping left hook in the 15th round, the exclamation point to his unanimous-decision victory.

An oversight? Or is Ali's legend-sustaining machinery served only by tapes that reveal him in the most favorable light?

Papa said Ali-Frazier I can't be shown on ESPN Classic because ESPN does not own the rights to that fight. Fair enough.

Still, there sometimes appears to be a revisionist history, one in which Ali's stature continues to expand even as Frazier's contracts. And it shouldn't be that way. These two warriors engaged in boxing's most riveting rivalry, which should have ensured ring immortality for both in near-equal measures.

Instead, on Jan. 12, Frazier turned 63 to little or no fanfare.

"It's always that way," Pete Lyde, Frazier's son-in-law, said of the widening gap in the way Ali and Frazier are perceived.

Lyde said he hoped to put together a "private event" for Smokin' Joe's family and friends, "maybe a couple of hundred people" at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, but it didn't come off.

"I'd like to do something really nice for him, maybe black-tie, at some point," Lyde said. "If anyone deserves it, it's him."

But while a meaningful celebration of Frazier's place among boxing's greatest champions remains on the drawing board, Ali has been more recognized and saluted than any king or potentate.

The multimillion-dollar Muhammad Ali Center, in Ali's hometown of Louisville, Ky., was the site of a one-year anniversary gala on Nov. 19, 2006, with 7,000 in attendance.

Ali has been lionized in a 1996 documentary, "When We Were Kings," which details his `74 upset of Foreman, and in a 2001 feature film, "Ali," which starred Philadelphia native Will Smith in the title role. Another documentary, "Louisville's Own Ali," has been shot.

Make no mistake, Ali's journey has been an incredible one. We might not see his like in boxing again. He left the footprints of a giant, and it seems impossible that the lithe, loud athlete of our memories is now a quaking sexagenarian afflicted by Parkinson's disease.

Perhaps Frazier has served to damage his own cause with a bitterness that traces back to the 1970s, when Ali belittled him, unfairly, as a "gorilla" and an "Uncle Tom." The verbal jabs stung Frazier, more than Ali's jabs inside the ropes, and the hard feelings that sprang from the feud linger to this day.

When Ali came out to light the Olympic flame in Atlanta in 1996, Frazier remarked, "I wish I could have pushed him into the fire."

It's good public relations for Frazier to settle his decades-old beef with Ali, who has become a cherished figure, especially when viewed through the soft lenses afforded him by ESPN Classic and others. A year or so ago, Frazier vowed to reconcile with Ali, but it's apparently difficult to reverse 30-plus years of animosity.

And it's not just Ali who's a thorn pricking Smokin' Joe's pride. A statue of the fictional Rocky Balboa now permanently sits at the base of the Art Museum steps. Ask most people around the world to name the figure who best exemplifies Philadelphia's rich boxing history, and they're apt to say Rocky.

Meanwhile, there is no statue of Joe Frazier to be found in Philly, where he has lived since he was 16.

But Frazier's displacement by Sylvester Stallone's celluloid creation is another story for another day. This tale of two January birthdays, one largely ignored by the masses and another lovingly presented for public inspection, reminds us that history is not always an accurate accounting. More often, it's what the most compelling storytellers get succeeding generations to believe.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Halberstam reflected on a battle Frazier is unlikely to win.

"Technically the loser of two of the three fights, he seems not to understand that they ennobled him as much as they did Ali, that the only way we know of Ali's greatness is because of Frazier's equivalent greatness, that in the end there is no real difference between them as fighters," Halberstam wrote

HBO SPECIAL ON THE FRAZIER ALI 1 FIGHT

HBO has done some extraordinary things over the last few years in the area of sports documentary -- if they ever establish an HBO Sports Film Library I'll be the first to join. But the upcoming "Ali-Frazier I: One Nation ... Divisible," which debuts Thursday, is on a whole new level. With all due respect to the much-honored documentary about the Ali-Foreman fight, "When We Were Kings," "One Nation ... Divisible" has the best subject for a boxing film imaginable: the social, political and personal turmoil that swirled around the first-ever meeting of two undefeated men who both claimed the heavyweight championship.

Actually, the social and political ends have been handled fairly well in print over the years, starting with Norman Mailer's seminal essay "King of the Hill," published in 1971, a few months after the March 8 fight, on up to the recent "Muhammad Ali Reader" and David Remnick's "King of the World," though we can all do with seeing some actual films of anti-war demonstrators and draft demonstrations again. What is unique in "One Nation ... Divisible" is how it makes clear the degree to which the personal relationships between Ali and Joe Frazier propelled the fight into what one of the on-screen commentators calls, and for once without hyperbole, "The greatest sporting event of the 20th century."

But for the politics of Vietnam (embodied in Ali's refusal to be inducted into the Army) and race, the truth is we would not remember the fight today if Ali had caved in early, or if he had stopped Frazier on cuts in, say, the fifth round. Yes, we remember the fight because of the politics, but watching "One Nation ... Divisible" I realized we also remember the politics -- or at least I can now discuss them with the younger kids in my family -- because they led to a great fight.

And, as the highlights at the end of the film make clear, it was a great fight, the greatest heavyweight championship fight of all time. Never before had two big (well over 200 pounds) men this skilled and determined, both with claims on the heavyweight title, fought so hard for so long. I've watched all the tapes of great fighters -- Dempsey and Tunney were one-sided except for the brief excitement of the "long count" in the second bout; Joe Louis and Billy Conn was great only because an overmatched light heavyweight fought over his head; and Jersey Joe Walcott and Rocky Marciano was fought by much smaller men.

Ali-Frazier could never happen again. For one thing, it went 15 full rounds, and title fights today are 12 rounds. For another, there's the competing alphabet title holders. Ali and Frazier didn't just claim the title belt of a particular political organization; because of Ali's three-and-a-half-year layoff and subsequent court battles, by 1971 he and Frazier had equally good claims to all belts from all organizations.

What "One Nation ... Divisible" makes brutally clear is the degree to which such a highly charged political event was animated by personal animosity. Or, more correctly, by what one of the two men regarded as betrayal. It has long been known that Ali and Frazier were friends before the pre-fight publicity barrage began, but no one brought the point home by talking to the fighters (or, in this case, the fighter, since Ali is in no shape to talk) about this. Frazier had volunteered his support to Ali when the U.S. government blocked his moves to get back in the ring. Frazier told him, "Whatever it takes, I'll help," and at one point gave him $2,000 to pay his hotel bills when Ali was down on his luck.

But when Ali began to campaign for the only big money fight out there -- Frazier -- he ignored Frazier the man and began pummeling the object. Frazier became an "Uncle Tom" and "The White Man's Champion" -- which was certainly true to a certain extent, but became all the more so because Ali made it so. Frazier, who had picked cotton as a boy in South Carolina and who dropped out of school to butcher meat in Philadelphia, had lived a life far closer to that of most American blacks than the relatively sheltered, middle-class Ali. All of a sudden, in the words of one of Ali's biographers, Frazier "became a symbol of Ali's oppressors."

One simply can't write off Ali's behavior as an attempt to sell tickets. The open cruelty of Ali's campaign (mocking Frazier's speech and flattening his nose to look like Frazier's) has never been fully acknowledged by his many biographers and admirers. Frazier clearly envied Ali; is it possible Ali was jealous of Frazier, jealous that he had actually lived the life of oppression that Ali didn't begin to discover until he was a teenager and found out what segregation meant?

Muhammad Ali is the most written-about sports figure who ever lived, but as "One Nation ... Divisible" makes clear, we don't entirely know him yet.

THE THRILLA IN MANILA

Joe you are the greatest

SMOKIN JOE'S BIO

Smokin Joe Frazier links

Fire of Joe Frazier:

Joe Frazier hof:

JOE FRAZIERS NIGHT

JOE FRAZIER UNDERRATED